Reclaiming Stereotypes the Malcolm McLaren Way

The 'Fagin of Punk' was hardly a 'self-hating Jew.'

In 1655, Oliver Cromwell reversed the decision made by Edward I in 1290 to expel all Jewish people from the Kingdom of England. 182 years later, Charles Dickens began publishing what would become one of the most popular works of English literature: Oliver Twist, the story of an orphan boy who finds himself caught in the criminal web of the greedy, murderous Jew known as Fagin.

Ever since Oliver Twist’s first publication as a serial in 1837, many Jewish people have rightly derided Fagin as an antisemitic caricature. Malcolm McLaren, the self-proclaimed swindler who brought punk to England, was not one of them.

When I first began working on my current project, a video that aims to shine a light on the overlooked Jewish history of early British punk rock, I figured it would be rather simple. Write about how Richard Hell and Lou Reed helped shape the look and attitude of the scene, highlight how Malcolm McLaren and Bernard Rhodes set the whole thing up and added in the left-wing politics, and point out how punk attracted outsiders so that Jewish people, the ultimate outsiders, naturally felt right at home. It would be a lighthearted, straightforward video that would teach the audience about how Jewish people helped shape the culture of British punk and why that shouldn’t be ignored when discussing the history of the subculture.

But then I realized I’d have to talk about the usage of the swastika in early punk art, one of the most reviled aspects of the scene, and why McLaren, who brought the trend across the pond from New York City to London, was so fixated on it. And then I realized I’d have to talk about how McLaren played with Jewish stereotypes when it came to how he presented himself to the public. There’s no way to properly analyze McLaren’s work and his contributions to punk without discussing his complex relationship to his Jewishness. Hardly lighthearted, straightforward, or simple, but a task I’m more than willing to take on if it means doing this topic the justice it deserves.

During one of the interviews I conducted for the video, Vivien Goldman, former Sounds journalist and member of The Flying Lizards, told me that she believed that McLaren was a ‘self-hating Jew’, a term that can mean several different things depending on who’s using it. Unfortunately our conversation moved on before I could ask her to expand so I don’t know Goldman’s personal definition of the term. For the purposes of this article, I’ll be using the definition given by psychologist Kurt Lewin, who popularized the term in the United States with his 1941 essay Self-Hatred among Jews. Lewin defined the phenomenon of Jewish self-hate as Jewish people, who have been designated as ‘the other’ and targeted for discrimination by gentile society, resenting or distancing themselves from all things Jewish. In other words, it’s the phenomenon of internalized antisemitism.

Let’s get one thing straight: everyone has the right to have a complicated relationship with their culture and identity. We have no right to judge someone based on our own notions of what being a ‘good Jew’ is. But what we do have a right to judge someone on is bigotry. No one, no matter how complicated their relationship to Jewishness is, has an excuse to be antisemitic.

So was Malcolm McLaren afflicted with internalized antisemitism? Was his obsession with playing with stereotypes and Nazi imagery coming from a place of disdain for his own people?

Short answer: no.

But since we’re here, let’s dive into the long answer.

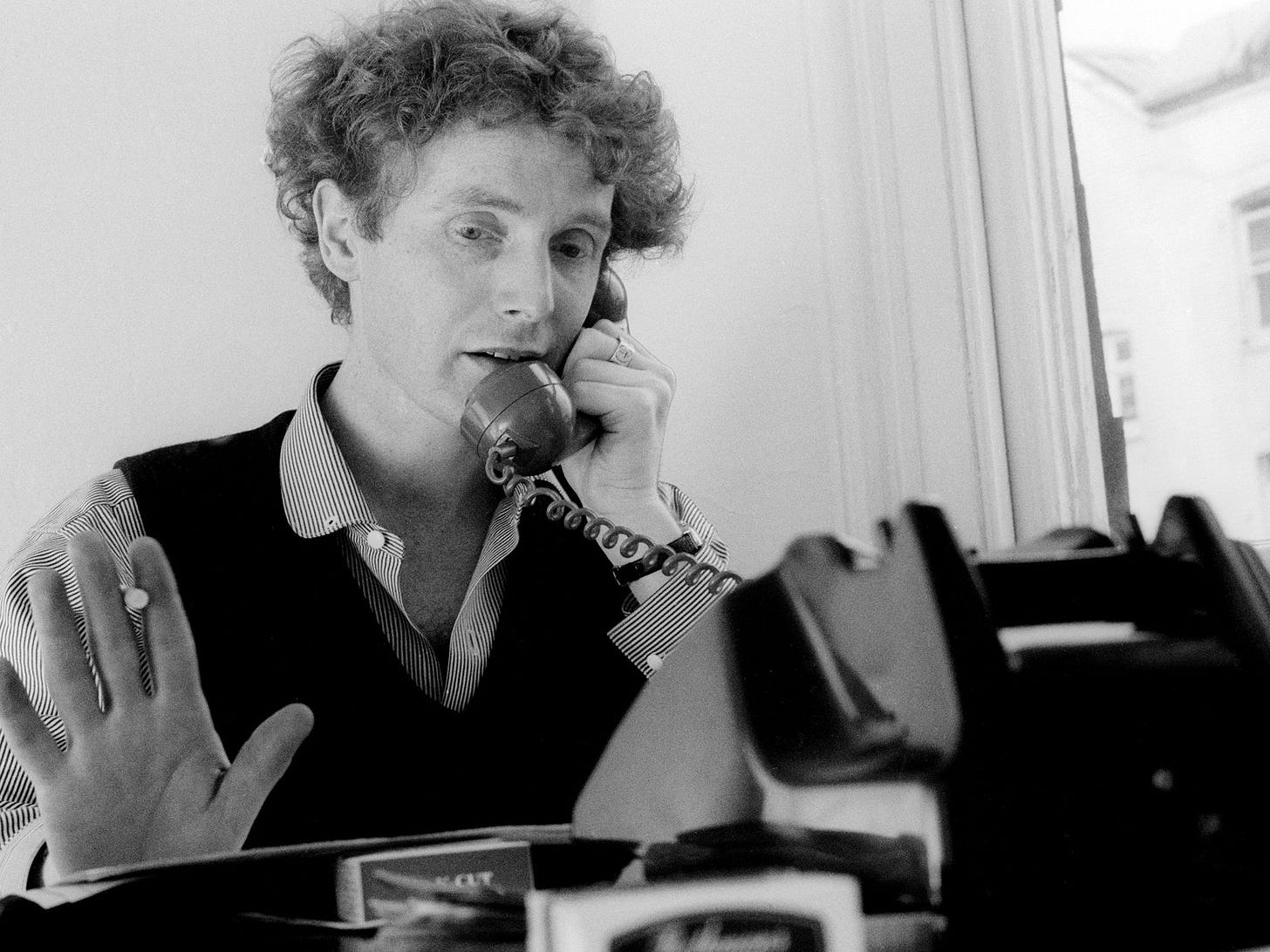

Born on January 22nd, 1946 in Stoke Newington, London to the unlikely pairing of Emily Issacs, the hard partying daughter of an upper class Sephardic family who’d immigrated to England from Amsterdam in the 1860s, and Peter McLaren, a working class Scottish gentile with a less than stellar reputation, Malcolm McLaren’s childhood was anything but conventional.

His parents separated only eighteen months after their marriage was certified. Issacs’ mother, Rose Corré, immediately inserted herself into young Malcolm’s life as his primary caretaker and kept his parents' influence on him extremely limited. Rose, who boasted that the Corré family were descendants of the Portuguese aristocracy, was captivated by her grandson’s curly red hair as, in her mind, it provided a direct link to their noble ancestry. She became determined to mold him in her eccentric image and began instilling within him the strange values that governed her life.

“To be bad is good, because to be good is simply boring,” was the motto that Rose imparted onto her grandson. She cultivated an anti-authority attitude within him by encouraging him to ignore his teachers at his strict Jewish parochial school and lavishing him with affection whenever he misbehaved in class. When he wasn’t in school, Rose provided Malcolm with an at-home curriculum of Charles Dickens.

Though Rose Corré wasn’t particularly religious, she was incredibly proud to be Jewish. Unlike most Jews, Rose responded to the cruel stereotypes rife in British culture by reinterpreting and taking ownership of the characters that embodied them, to the point of giving them a new life beyond the text. When she read Oliver Twist to Malcolm, she explained to him that Fagin, the miser with no qualms about letting the children he leads into criminality get sent to the gallows, was the true hero of the story. According to Rose, Fagin was based on a real person that Dickens had met and, since no one as intelligent as Fagin would ever be caught and hanged, this real person actually escaped to Australia where he lived out the rest of his life rich and happy. She also told Malcolm that Ebenezer Scrooge, another miser from a Dickens novel who is often speculated to be a ‘crypto-Jew’ due to his hooked nose and Hebrew name, was worthy of admiration as well. Through these characters, Rose taught Malcolm how to live outside of the laws of gentile society and create his own world.

“My grandmother picked these books because they were her favorites and she thought they could teach me something about life. Of course, her take on them was a little unconventional and probably quite different from what I would have been told about them had I read them back in that regular school.”

[...]

“Everyone knows that Fagin was a Jew, and critics have long suspected Scrooge was the same. While Dickens meant them to be antisemitic caricatures, my grandmother saw them as antiheroes who were the true focus of the story. She loved them because they reflected her own view of life. ‘Don’t ever talk to a policeman,’ was her motto. ‘A Jew has nothing to do with the police.’ And she wasn’t the only one to think that way. Where I grew up, that was the attitude. We lived in a world that was separate, apart.”

– Malcolm McLaren, The Heebie-Jeebies at CBGBs

English culture enforced a downplaying and shame around Jewishness. Though England had allowed them back into its borders, Jewish people were merely tolerated, not embraced or welcomed into society. To quote the English Jewish poet A. Alvarez, “no matter how long they stay, it never quite washes away the sense of being foreign. The only solution is disguise and impersonation, like spies in deep cover.” With this in mind, Rose’s reclamation of these antisemitic caricatures can be read as her taking pride in her Jewishness and rebelling against the rules imposed on her by a society that encouraged assimilation.

Thus McLaren’s later evocation of Fagin did not necessarily have to spawn from any sort of self-hatred or a desire to humiliate the culture he grew up in. More likely it maintained a unique sense of pride that he inherited from his grandmother, which found power in reclaiming ugly stereotypes and turned anti-social defects into anti-establishment resilience.

“The Sex Pistols—they were my artful dodgers, as I was their Fagin. So what am I going to say, “No, I’m not”? Of course, I am. And I’m actually quite proud to be.”

– Malcolm McLaren, The Heebie-Jeebies at CBGBs

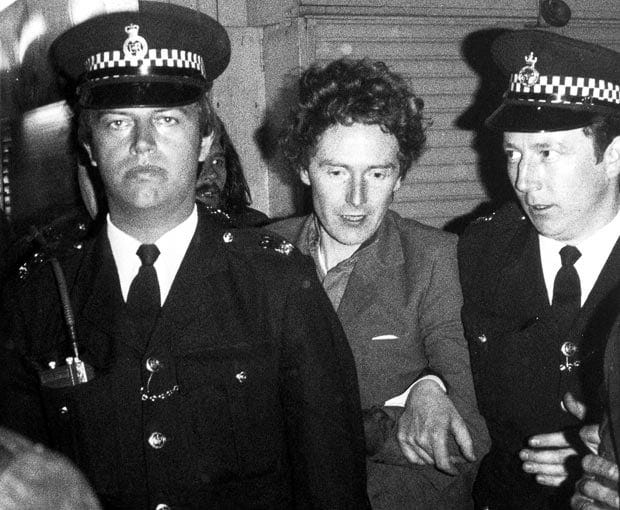

To McLaren there was nothing wrong with being a Fagin or, to bring up another antisemitic caricature from classic British literature that McLaren found himself a fan of, a Svengali. But he was well aware that many believed there was. During my interview with Paul Gorman, who wrote the definitive biography on McLaren, The Life & Times of Malcolm McLaren, he suggested that McLaren’s desire to connect himself to these characters was his way of sending up the antisemitic tropes they embodied. If the gentile public was going to think he was a manipulative, greedy Jew who was leading innocent English children down the path of sin no matter what he did, then he might as well turn those stereotypes up to eleven just to rub everyone’s noses in them. His opening monologue in The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle is the ultimate example of this, where McLaren puts on a London Yiddish accent and claims full ownership over the youth movement he helped create.

When interviewed for the 2004 documentary Blood on the Turntable, McLaren asserted that his Fagin persona was exactly that– a persona. He seemed baffled that people actually believed that the exaggerated character he performed for the cameras was the ‘real’ him. It’s not surprising that this social satire went over people’s heads. The distrust towards Jewish men runs deep in Christian societies. The public is far more likely to nod along and say “I knew it” when a Jewish man claims he did it all for the money than to look deeper. To this day, people echo McLaren’s glib assertion that he managed the Sex Pistols just to sell more clothes and insist that The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle expresses McLaren’s honest opinions on punk.

"That film caused punk to become an enigma, tried to prevent it becoming just another page in the rock'n'roll almanac. Going down in history as criminals all bent on destroying the music industry. That was our way of having the last laugh. It's a mad film, innit? Completely mad!"

– Malcolm McLaren, GQ Magazine

But what about McLaren’s fixation on the swastika?

According to my friend Mark Jay, filmmaker and creator of the SKUM fanzine back in 1976, as well as the ‘The Story So Far’ poster for the release of the Sex Pistols’ debut LP, when it came to McLaren and the swastika, it had everything to do with his artistic and political philosophies.

McLaren was a believer in Situationism, the avant-garde strain of Marxism developed by Guy Debord in 1957 which encouraged artists to create situations that would inspire the public to think deeper about the world around them. Radical, shocking, and self-contradictory messages and imagery would wake people up to the convoluted, media-arbitrated landscape they were sleepwalking through.

McLaren participated in Situationist groups such as the King Mob Gang throughout his art school days and drew upon Situationist ideas for the art he created with Vivienne Westwood at 430 King’s Road, along with their longtime partners in crime Jamie Reid and Helen Wellington-Lloyd. Their goal was to provoke and disturb, to open up discussions about the most taboo topics in society in hopes of liberating people from the repression of British society.

The images in McLaren-Westwood designs confronted sexuality, gender, race, and politics. From two muscular cowboys with their exposed crotches touching to the Cambridge Rapist’s mask above a news clipping of Brian Epstein supposedly dying during a sexual misadventure, nothing was off limits. And that included the swastika.

The swastika has been one of, if not the most globally reviled symbols since the beginning of World War II. To this day, the swastika is invoked to threaten and alienate marginalized groups, especially Jewish people. Naturally, McLaren’s repeated use of the swastika and other Nazi imagery is one of the most controversial aspects of his work. But let’s try to look at the way he and his collaborators used it with an open mind.

The McLaren-Westwood designs that evoke Nazi imagery the most prominently are the ‘Destroy’ shirt and the ‘Anarchy’ shirt:

As seen above, the swastika is not alone in these designs. On the ‘Destroy’ shirt, an upside down Christ on the cross and the beheaded Queen of England are emblazoned over the swastika, with the word DESTROY above them all. On the ‘Anarchy’ shirt, the Nazi eagle is upside down (a feature of other McLaren-Westwood designs) and displayed with a picture of Karl Marx, a red CHAOS armband, a Situationist slogan, and vertical stripes reminiscent of the uniform concentration camp inmates were forced to wear (a detail that would be copied by fellow Jewish punk Mick Jones for another shirt.)

By juxtaposing these loaded images, these designs elide accusations of being celebratory usages of Nazi imagery. To quote Mark Jay, “juxtaposition of seemingly disconnected imagery is a Situationist tactic, intended to dismantle and disempower symbols of oppression by re-contextualising, re-grouping, and ironically commodifying them in a way that is directly confrontational.”

When McLaren and Westwood placed Jesus, The Queen, and a swastika all together underneath the word destroy or turned the Nazi eagle upside down, the message was clear. At least, it was to them. Where McLaren, Westwood, and their collaborators saw a left-wing, anti-authoritarian statement that was as far from an endorsement of Nazism as one could get, others saw approval or trivialization of Nazi ideology.

Neo-Nazis like the National Front saw the usage of the swastika as encouragement to insert themselves into the punk scene in order to recruit new members to their organizations. Meanwhile the marginalized groups targeted by those organizations often found themselves being put off, not wanting to find out the hard way which punk bands believed in the ideals that the swastika historically stood for.

“Malcolm always said of the ‘Destroy’ t-shirt that he was making a general point about leaders, which was a bit too subtle for the average NF or even the average punk. It was a pipe dream.”

– Sophie Richmond, England’s Dreaming

It was an incredibly foolish decision to use Nazi imagery during an era when the extreme far-right was on the rise, one that would cause countless problems within the punk scene for years to come, but we shouldn’t ignore the context behind what McLaren and Westwood were trying to do. There was a method to their madness that shouldn’t be overlooked, as well as a message that still rings true to this day.

So what to make of all of this? That’s up for you to decide. Personally, I think Malcolm McLaren was a proper mensch. I find no self-hatred and certainly no disdain for his fellow Jews when I look at the tapestry of his life. Aside from what’s already been mentioned, he admired fellow Jews in the industry like Larry Parnes, Sylvain Sylvain, and Richard Hell, and collaborated with other Jewish artists. As far as I see it, he was proud to be Jewish. He didn’t show that pride in the most conventional way, but nothing about Malcolm McLaren was conventional – if it was, he never would have changed the world.

“There was no question that it was easy for me to find my artful dodgers, my Sex Pistols, [and] to behave like Fagin, to behave like Svengali. It all came naturally. This was my childhood. This is how I was brought up. This was my world, my anti-world if you like; not the real world outside, but the anti-world that my grandmother painted and that she felt had virtues and feelings that I was going to continue.”

– Malcolm McLaren, The Heebie-Jeebies at CBGBs

Sources:

Beeber, Steven Lee. The Heebie-Jeebies at CBGB's: A Secret History of Jewish Punk. Chicago Review Press, 2006

Gorman, Paul. The Life & Times of Malcolm McLaren: The Biography. Constable, 2020

Savage, Jon. England's Dreaming, Revised Edition: Anarchy, Sex Pistols, Punk Rock, and Beyond. St. Martin's Griffin, 2002

Gerson, Jordie. “Self-Hating Jews.” My Jewish Learning, https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/self-hating-jews/

“Malcolm McLaren: ‘I don't mind being accused of being the Fagin, in many respects I was’.” GQ Magazine, https://www.gq-magazine.co.uk/article/malcolm-mclaren-sex-pistols-interview

Blood on the Turntable. BBC Three, 2004

“Let’s get one thing straight: everyone has the right to have a complicated relationship with their culture and identity”. One of the best sentences I’ve read in a long time.

You trace convincingly that

Malcolm’s “Jewishness” came via a contrarian family member and Dickens.

Combining the political framing of your opening and the complexities of personality, are there any strains of his Jewishness that may have been borrowed/sampled from Disraeli?